"The Embrace of Locality"...Whitney Biennial 2008

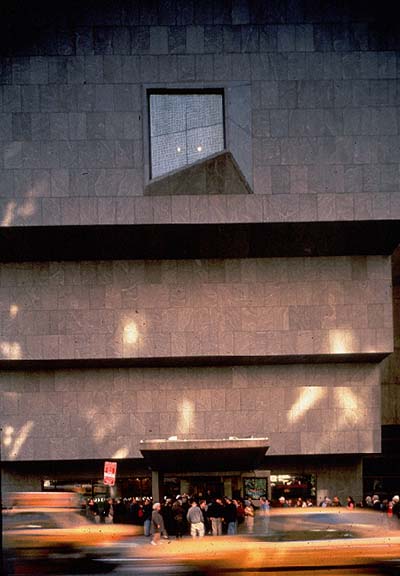

Despite a long history of attempts, including the Michael Graves postmodernist fiasco of 1985 and a Rem Koolhaas proposed tower that was scrapped in 2003, the museum has thus far been denied its grand gesture, and has only been able to complete useful but minimal initiatives, such as the incorporation of two adjacent brownstones for offices and other administrative functions. This stalemate might change with the construction of a Renzo Piano designed downtown branch abutting the High Line, where the Dia Foundation once planned to re-settle. But for the moment, the Whitney remains five floors of an inverted Marcel Breuer ziggurat on Madison Avenue and

After many years attending shows, and not just Biennials, in this same landmark building, a sense of familiarity and trust develops. The museum’s physical plant has an obvious but reassuring constancy: the flagstone floors, the honeycombed ceilings. One remembers previous layouts and alternate selections of art, different walls for different sprawls, other work placed near the trapezoidal windows, other uses of the sunken courtyard, other displays in the glass case near the (woefully inadequate) second floor screening room. The Whitney’s “failure” to expand has, perhaps counter-intuitively, had a positive influence, engendering good will that might have been lessened or lost had the museum embarked on the same hubristic will to super size that enticed its sister institutions.

We enjoy the Whitney for its scrappy, resourceful independence, for managing to do a lot with a little. There is not just a legacy of excellent, well curated shows, which seem to place art first rather than running after blockbuster content (with the occasional lapse, like last summer’s psychedelic extravaganza) but also a modesty of scale and intention, as embodied in the clever, contained modernism of its 1966 Breuer building.

Who can blame the museum for wanting to stretch out a bit at this time, at this moment of maximum visibility? Previous editions of the Biennial have incorporated outdoor sculpture in

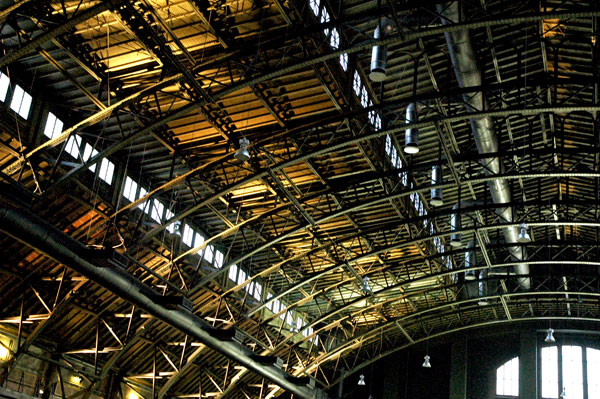

Occupying a full square block, with a central Drill Hall five stories high and an enclosed area better measured in acres than square feet, the Armory dwarfs the museum proper. It would seem to answer every artist’s secret wet dream: space, space, glorious space, in a city where real estate options for studios range from the challenging to the impossible.

The Armory is built on a baronial scale, with charming anachronisms of nineteenth century architecture and ornamentation: dark wood paneling and wainscoting, elaborate arched transoms and doorways, chandeliers, wide halls, double staircases, glass enclosed cabinets full of silver cups and urns, long unused wooden lockers, military flags, bunting and portraiture, all the pomp and panoply of a forgotten era.

It is also falling apart. Its patched ceilings and walls, ancient electrical wiring and other building systems need replacement, and are slated for massive renovation, so that the Armory can become a more useful and attractive space for a full calendar of art projects. Once that occurs, one wonders what will happen to its current roster of temporary residents who occupy the women’s shelter housed on its third and fifth floors.

But in its current incarnation, still a bit dilapidated and physically distressed, the Armory feels like the anti-Whitney: dark, decaying, somber and old, decidedly not adhering to the usual exhibition model of a clean white cube. It resonates as a haunted house, a locus of the unconscious mind with creaky floors and untrammeled visions. Despite its address of Park Avenue and 67th Street, not exactly the poorest part of town, the Armory manages to recapitulate the history of artists as battering rams for real estate: moving into questionable neighborhoods and compromised buildings, into cold water tenement flats and windy industrial lofts, with leaks and holes and rotting fixtures, and making these places useful again, at first just for their creative enterprise, as reclaimed enclaves for the demimonde, but eventually “safe” for general use and for the enrichment of speculators.

The Armory, then, is not just extra space to house the Biennial. It connotes an entirely different sort of space. If the museum is the quintessential white box, where finished work winds up, where its importance and art historical value can be measured in a cool, clear, antiseptic light, then the Armory is emblematic of the studio, a place much closer to the actual moment of creation, more “honest”, more “immediate”, more revelatory of praxis. Also clubbier, more bohemian, fecund and feral: what Kurt Cobain was talking about in “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. A place where artists can engage in ephemeral acts, where they can feel unhampered, where they can fail and try again, where they can cavort and play as we, lucky mortals, watch them do so. A place to see the art before it is complete, perhaps before it has even been imagined. A funky incubator.

The Armory, then, is not just extra space to house the Biennial. It connotes an entirely different sort of space. If the museum is the quintessential white box, where finished work winds up, where its importance and art historical value can be measured in a cool, clear, antiseptic light, then the Armory is emblematic of the studio, a place much closer to the actual moment of creation, more “honest”, more “immediate”, more revelatory of praxis. Also clubbier, more bohemian, fecund and feral: what Kurt Cobain was talking about in “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. A place where artists can engage in ephemeral acts, where they can feel unhampered, where they can fail and try again, where they can cavort and play as we, lucky mortals, watch them do so. A place to see the art before it is complete, perhaps before it has even been imagined. A funky incubator.

It hardly matters whether an installation at the Armory is any less studied or self conscious than similar work at the Whitney proper. The pose is all. The iconography of the Armory as a venue is part