Lee Wells and the Blowback of Empire Porn

LEE WELLS: ACTION FOR FREEDOM

ROOSTER GALLERY, 190ORCHARD STREET, NYC

FEBRUARY 17 – MARCH 12, 2011

Pirate Flag #2, 2010, HD Video, 10 minutes

Pirate Flag #2, 2010, HD Video, 10 minutes

Wikipedia: Blowback is the espionage term for the violent, unintended consequences of a covert operation that are suffered by the civil population of the aggressor government. To the civilians suffering the blowback of covert operations, the effect typically manifests itself as “random” acts of political violence without a discernible, direct cause; because the public—in whose name the intelligence agency acted—are ignorant of the effected secret attacks that provoked revenge (counter-attack) against them.

---------------------------------------

What's in a name? "Action for Freedom", the generic, boosterish title of Lee Wells' new exhibition of paintings and recycled digital video, at first sounds like a grassroots community organization, a vigilante committee, even a policy wonk's think tank. But those two fully loaded buzzwords, which might suggest engagement or advocacy in another context, are defused here, rendered open-ended and non-specific. Like other bland amalgams which tend to litter the political landscape - could Wells have titled his exhibition "New Republic" or "National Review"? - the connotation is intentionally ambiguous. Only further examination allows us to understand that one magazine is firmly located on the left of the political spectrum, the other just as forcefully on the right. But nothing in the names themselves would signal this partisanship. It is a convention rooted in usage.

Similarly, you would need to walk a mile in Wells' shoes to appreciate his particular stance. So heft that pack, soldier, and shoulder your rifle. Twenty years ago, Wells served in the US Army and just missed being shipped off to the First Gulf War by a couple of days. He experienced the military from the inside, and his ambition as an artist is to present images of American Imperial Porn as perceived by the grunts on the front lines, the MPs in the stockade, the guys driving the Humvees and the APCs. By porn, we're not just referring to the usual adrenaline-laced wash of sex and violence. Rather, it's the immersive pornography of empire building, of logistics and combat and expeditionary forces, of asymmetrical warfare, of Islamic fundamentalist customs clashing/melding with the imperatives of the West.

Back in the salad days of the British Empire, imperialism was succinctly defined by Rudyard Kipling's apologia of the "white man's burden". But this rationalization has become a bit outdated in recent years, as the military undertakes a more nuanced approach, hoping to win over the hearts and minds of occupied nations. Thus the porn of IEDs, RPGs and military jargon handily conflates with local practices from the Arab street. The porn of kitsch, of YouTube videos, ofFacebook friends and tweets and shared music files, characterizes the Internet/entertainment complex of both the contemporary American GI and the wired indigenous population. While we might pray to different gods and eat separate meals, online we are all plugged into the same big motherboard.

Perhaps due to this grand commonality, "Action for Freedom" is a strange jumble of an exhibition, ambitious in scope yet seemingly offhand in its presentation. Just like the Internet, it can feel both casual and contrived, aleatoric but designed, open-ended yet framed. Through his own example, Wells seems to argue for net neutrality and open sources. He appears ready and willing to incorporate content from just about anywhere. As was true in his Perpetual Art Machine project, which compiled artists' videos in a cross referenced grid, Wells is a benign gatekeeper, presiding over a revolving door that allows images to flow from upload to download and back again, crossing national, cultural, corporate and oligarchical barriers as if these were invisible. Or perhaps to argue for that very invisibility.

In this sense, another appropriate title for the show would be "Blowback". The usual connotation of the term, in our post 9/11 world, regards Islamic terrorism on American soil and against American civilians as revenge exacted by Al Qaeda to punish the US for its Middle East policies. And this certainly remains a large part of the equation. But just as with the definition of porn, blowback can more meaningfully encompass a larger dialectic: the sharing, mangling, and interweaving of cultural content that accompanies invasion, war and occupation. It is a blending of cultural referents that arrive from the hinterlands to "contaminate" the seat of imperial power -- much as Christianity can be seen as a virus that migrated from ancient Judea to infect Rome -- creating a New World Order of signifiers, a global set of referents, codes and memes that delimit our shared information superhighway.

This is the context which most interests Wells in his dissection of Empire Porn. But as is sometimes the case with "cutting edge" work, the knife is able to cut both ways. This exhibition is given added, immediate relevance by current events, by the recent spate of democratic, street revolutions that have ignited across the Arab world, which were at least partly facilitated byFacebook , Twitter and other social networking sites that helped spread the spark of popular revolt, despite attempts by certain governments to shut them down. Obviously, "blowback" is really "blow back and forth". The Internet is a tool , but also a weapon. And once things go viral, they might easily infect the regimes of Mubarak or Qaddaffi with a flu for which there is no cure.

Lee Wells with his portrait of Pat Tillman.

Let's begin in the basement of Rooster Gallery, since every show should have a solid foundation, but also because this was the gallery I visited first. It is dominated by a large portrait of Pat Tillman, the soldier's soldier, a college linebacker and pro football star who left all that behind to enlist in the Army Rangers, and who died in 2004 in the mountains of Afghanistan -- from friendly fire, as it turned out, despite a government cover-up that initially misinformed both his family and the general public. The official, heroic composite portrait, in full color, shows Tillman standing square jawed and resolute in front of a furled American flag, his name and the markings on his tunic blacked out (as a funerary gesture? or for security considerations?). Wells modifies this, rendering it in grisaille to increase the sculptural presence, but also to emphasize the shifting shades of gray that have characterized the government's mishandling of the truth about the death. It is a potent, ambivalent image. While we must laud Tillman's All-American patriotism and supreme sacrifice, the total story conjures up an unfortunate saga of US Army duplicity, their attempt to sweep the ugly, messy specifics of combat under the carpet for the sake of the propaganda machine: to make Tillman a Silver Star poster boy for uninflected, knee jerk patriotism.

The basement series of hooded houris.

On an adjoining wall, posed like the harem of the heroic warrior (those 72 black eyed virgins promised to martyrs in heaven?), are six painted images of women, each of whom wears a single article of clothing, the Islamic veil or hijab, but little else. They are splayed in various expectant postures of sexual availability, with slim hips, pert nipples and eyes staring -- seductively? insouciantly? defiantly? -- through the slits of their headgear. One even gives us the finger, with both hands.

My initial assumption, as the women seem similar from piece to piece, was that Wells organized a shoot with a single model and used the resulting photographs as the basis for his paintings. In fact, he claims to have searched assiduously online, scouring the Internet for just these images, which he found on a variety of websites, both Islamic and Western. Some are apparently taken from Muslim sex sites, advertising Arab-on-Arab kink or Turkish delight. Others seem to be domestic products, outcroppings of the great Los Angeles porn industry that employs the veil as just another bit of fetish wear. Some might be favorites of the American GIs stationed in the Middle East, inflamed by the beauty and exoticism of the local houris: typical red blooded American boys out for a quick romp with the Islamic homegirls.

Veiled Woman #4, 2011, oil on canvas, 14 x 11 inches

Others might be viewed as consciously blasphemous, challenging the strictures of Islam, seeking to violate the traditional modesty and morality advanced by the wearing of the hijab. And others, especially if the work is diaristic or employs the image of its creator, can be seen as self-empowering: Muslim women attempting to throw off the veil as a lingering vestige of the overbearing patriarchy. Or Western feminists using the veil for a bit of agitprop theater. (As in: "OK. We'll wear your hijab. But nothing else.")

Depending on their sources, these provocative images could suggest a whole panoply of intentions. But the only context given is a series of painted images arranged in a row on the wall. They are presented as sisters in flagrancy, a gang of randy yet mysterious signifiers, sexually titillating but opaque to interpretation. Wells maintains the anonymity of the Internet and the open source, leading to broad conjecture on these veiled women. (Writer's confession: It was while viewing these particular works that the term "Empire Porn" first came to mind.)

Ballistic Trauma #1, 2011, oil on panel with video on custom multimedia player, 24 x 20 inches

All work discussed thus far is found in the basement: the appetizers, if you will. Upstairs in the storefront proper is the main course, a series of wooden panels, painted desultorily in generic expressionist abstraction reaching for incipient figuration, but each with a jagged, irregular hole gouged through the middle -- reminiscent ofWilliam Burroughs ' technique in his shotgun paintings from the 1980s. Burroughs was happy to blast away at his aerosol spray paint cans and make them spew paint on canvas, essentially using the shotgun as paintbrush, but for Wells the panels are just the beginning. They serve primarily as frames for LED screens that are installed beneath them, so that through each irregular hole we can view, peek-a-boo style, a program of videos that the artist has culled from the Internet.

Ballistic Trauma #4, 2010, Oil on panel with video on custom media player, 24 x 20 inches

The content of these videos encompass a full sampling of Empire Porn. They range from street demonstrations to torture sequences, from suicide bombers to the tentative exercise of free speech in the public sphere, from social unrest to police brutality, from terrorist acts to their fierce suppression, focusing on the militarization of society, the regimen of intimidation in prisons, the systems of permission and control that define a world viewed from the panopticon of the Internet. Each piece contains video images intercut from five sources, running in a continuous loop.

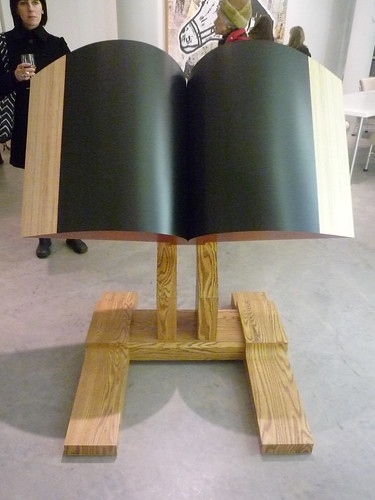

Completing the show is the Pirate Flag video, represented by the still image at the top of this article. Flapping in a fresh breeze off a Cape Cod beach, the flag seems iconic of the usual bad boy stereotype, but also defines Wells as a "pirate" of Internet content, a hunter/gatherer who scours the information superhighway for evidence of the transgressive, the revelatory, the enticing, the shameful and the expedient, for misbehavior and for the blowback of empire building that is always there, beneath the surface, waiting to snarl at us: "Arrrrrrrrghhh!"

As a parting example of blowback, allow me to share a message just received from Mr. Rafik Jihad, a gentleman I have never met (who could forget someone named "Jihad"?) and who I suspect might not actually exist outside my Inbox, but who identifies himself as a bank officer making a most generous offer. While some might deride this as pure, unadulterated spam, I prefer to see it as another instance of blowback from the Middle East. Perhaps Mr. Wells will soon incorporate phishing and identity theft into a body of work on the discontents of the new American empire.

Blunt Trauma #3, 2010, Oil and acrylic on panel with video on custom media player, 24 x 20 inches

ROOSTER GALLERY, 190

FEBRUARY 17 – MARCH 12, 2011

Pirate Flag #2, 2010, HD Video, 10 minutes

Pirate Flag #2, 2010, HD Video, 10 minutesWikipedia: Blowback is the espionage term for the violent, unintended consequences of a covert operation that are suffered by the civil population of the aggressor government. To the civilians suffering the blowback of covert operations, the effect typically manifests itself as “random” acts of political violence without a discernible, direct cause; because the public—in whose name the intelligence agency acted—are ignorant of the effected secret attacks that provoked revenge (counter-attack) against them.

---------------------------------------

What's in a name? "Action for Freedom", the generic, boosterish title of Lee Wells' new exhibition of paintings and recycled digital video, at first sounds like a grassroots community organization, a vigilante committee, even a policy wonk's think tank. But those two fully loaded buzzwords, which might suggest engagement or advocacy in another context, are defused here, rendered open-ended and non-specific. Like other bland amalgams which tend to litter the political landscape - could Wells have titled his exhibition "New Republic" or "National Review"? - the connotation is intentionally ambiguous. Only further examination allows us to understand that one magazine is firmly located on the left of the political spectrum, the other just as forcefully on the right. But nothing in the names themselves would signal this partisanship. It is a convention rooted in usage.

Similarly, you would need to walk a mile in Wells' shoes to appreciate his particular stance. So heft that pack, soldier, and shoulder your rifle. Twenty years ago, Wells served in the US Army and just missed being shipped off to the First Gulf War by a couple of days. He experienced the military from the inside, and his ambition as an artist is to present images of American Imperial Porn as perceived by the grunts on the front lines, the MPs in the stockade, the guys driving the Humvees and the APCs. By porn, we're not just referring to the usual adrenaline-laced wash of sex and violence. Rather, it's the immersive pornography of empire building, of logistics and combat and expeditionary forces, of asymmetrical warfare, of Islamic fundamentalist customs clashing/melding with the imperatives of the West.

Back in the salad days of the British Empire, imperialism was succinctly defined by Rudyard Kipling's apologia of the "white man's burden". But this rationalization has become a bit outdated in recent years, as the military undertakes a more nuanced approach, hoping to win over the hearts and minds of occupied nations. Thus the porn of IEDs, RPGs and military jargon handily conflates with local practices from the Arab street. The porn of kitsch, of YouTube videos, of

Perhaps due to this grand commonality, "Action for Freedom" is a strange jumble of an exhibition, ambitious in scope yet seemingly offhand in its presentation. Just like the Internet, it can feel both casual and contrived, aleatoric but designed, open-ended yet framed. Through his own example, Wells seems to argue for net neutrality and open sources. He appears ready and willing to incorporate content from just about anywhere. As was true in his Perpetual Art Machine project, which compiled artists' videos in a cross referenced grid, Wells is a benign gatekeeper, presiding over a revolving door that allows images to flow from upload to download and back again, crossing national, cultural, corporate and oligarchical barriers as if these were invisible. Or perhaps to argue for that very invisibility.

In this sense, another appropriate title for the show would be "Blowback". The usual connotation of the term, in our post 9/11 world, regards Islamic terrorism on American soil and against American civilians as revenge exacted by Al Qaeda to punish the US for its Middle East policies. And this certainly remains a large part of the equation. But just as with the definition of porn, blowback can more meaningfully encompass a larger dialectic: the sharing, mangling, and interweaving of cultural content that accompanies invasion, war and occupation. It is a blending of cultural referents that arrive from the hinterlands to "contaminate" the seat of imperial power -- much as Christianity can be seen as a virus that migrated from ancient Judea to infect Rome -- creating a New World Order of signifiers, a global set of referents, codes and memes that delimit our shared information superhighway.

This is the context which most interests Wells in his dissection of Empire Porn. But as is sometimes the case with "cutting edge" work, the knife is able to cut both ways. This exhibition is given added, immediate relevance by current events, by the recent spate of democratic, street revolutions that have ignited across the Arab world, which were at least partly facilitated by

Lee Wells with his portrait of Pat Tillman.

Let's begin in the basement of Rooster Gallery, since every show should have a solid foundation, but also because this was the gallery I visited first. It is dominated by a large portrait of Pat Tillman, the soldier's soldier, a college linebacker and pro football star who left all that behind to enlist in the Army Rangers, and who died in 2004 in the mountains of Afghanistan -- from friendly fire, as it turned out, despite a government cover-up that initially misinformed both his family and the general public. The official, heroic composite portrait, in full color, shows Tillman standing square jawed and resolute in front of a furled American flag, his name and the markings on his tunic blacked out (as a funerary gesture? or for security considerations?). Wells modifies this, rendering it in grisaille to increase the sculptural presence, but also to emphasize the shifting shades of gray that have characterized the government's mishandling of the truth about the death. It is a potent, ambivalent image. While we must laud Tillman's All-American patriotism and supreme sacrifice, the total story conjures up an unfortunate saga of US Army duplicity, their attempt to sweep the ugly, messy specifics of combat under the carpet for the sake of the propaganda machine: to make Tillman a Silver Star poster boy for uninflected, knee jerk patriotism.

The basement series of hooded houris.

On an adjoining wall, posed like the harem of the heroic warrior (those 72 black eyed virgins promised to martyrs in heaven?), are six painted images of women, each of whom wears a single article of clothing, the Islamic veil or hijab, but little else. They are splayed in various expectant postures of sexual availability, with slim hips, pert nipples and eyes staring -- seductively? insouciantly? defiantly? -- through the slits of their headgear. One even gives us the finger, with both hands.

My initial assumption, as the women seem similar from piece to piece, was that Wells organized a shoot with a single model and used the resulting photographs as the basis for his paintings. In fact, he claims to have searched assiduously online, scouring the Internet for just these images, which he found on a variety of websites, both Islamic and Western. Some are apparently taken from Muslim sex sites, advertising Arab-on-Arab kink or Turkish delight. Others seem to be domestic products, outcroppings of the great Los Angeles porn industry that employs the veil as just another bit of fetish wear. Some might be favorites of the American GIs stationed in the Middle East, inflamed by the beauty and exoticism of the local houris: typical red blooded American boys out for a quick romp with the Islamic homegirls.

Veiled Woman #4, 2011, oil on canvas, 14 x 11 inches

Others might be viewed as consciously blasphemous, challenging the strictures of Islam, seeking to violate the traditional modesty and morality advanced by the wearing of the hijab. And others, especially if the work is diaristic or employs the image of its creator, can be seen as self-empowering: Muslim women attempting to throw off the veil as a lingering vestige of the overbearing patriarchy. Or Western feminists using the veil for a bit of agitprop theater. (As in: "OK. We'll wear your hijab. But nothing else.")

Depending on their sources, these provocative images could suggest a whole panoply of intentions. But the only context given is a series of painted images arranged in a row on the wall. They are presented as sisters in flagrancy, a gang of randy yet mysterious signifiers, sexually titillating but opaque to interpretation. Wells maintains the anonymity of the Internet and the open source, leading to broad conjecture on these veiled women. (Writer's confession: It was while viewing these particular works that the term "Empire Porn" first came to mind.)

Ballistic Trauma #1, 2011, oil on panel with video on custom multimedia player, 24 x 20 inches

All work discussed thus far is found in the basement: the appetizers, if you will. Upstairs in the storefront proper is the main course, a series of wooden panels, painted desultorily in generic expressionist abstraction reaching for incipient figuration, but each with a jagged, irregular hole gouged through the middle -- reminiscent of

Ballistic Trauma #4, 2010, Oil on panel with video on custom media player, 24 x 20 inches

The content of these videos encompass a full sampling of Empire Porn. They range from street demonstrations to torture sequences, from suicide bombers to the tentative exercise of free speech in the public sphere, from social unrest to police brutality, from terrorist acts to their fierce suppression, focusing on the militarization of society, the regimen of intimidation in prisons, the systems of permission and control that define a world viewed from the panopticon of the Internet. Each piece contains video images intercut from five sources, running in a continuous loop.

Completing the show is the Pirate Flag video, represented by the still image at the top of this article. Flapping in a fresh breeze off a Cape Cod beach, the flag seems iconic of the usual bad boy stereotype, but also defines Wells as a "pirate" of Internet content, a hunter/gatherer who scours the information superhighway for evidence of the transgressive, the revelatory, the enticing, the shameful and the expedient, for misbehavior and for the blowback of empire building that is always there, beneath the surface, waiting to snarl at us: "Arrrrrrrrghhh!"

As a parting example of blowback, allow me to share a message just received from Mr. Rafik Jihad, a gentleman I have never met (who could forget someone named "Jihad"?) and who I suspect might not actually exist outside my Inbox, but who identifies himself as a bank officer making a most generous offer. While some might deride this as pure, unadulterated spam, I prefer to see it as another instance of blowback from the Middle East. Perhaps Mr. Wells will soon incorporate phishing and identity theft into a body of work on the discontents of the new American empire.

From Mr. Rafik Jihad,

Complement of the day to you and your beloved family. I apologize for this intrusion, I decided to contact you through email due to the urgency involved in this matter. Do not be astonished for receiving this mail. Please, I seek your permission and would want to get myself introduce to you. I am Mr. Rafik Jihad. I work with Islamic Development Bank (IDB). I need your co-operation in receiving USD$6.5M that has been in a dormant account with my bank for 5 years which belongs to one of our foreign customer who died along with his entire family during the Iraq war in 2006. I will provide you with detailed information's on the modalities of this operation once I have your interest but I must say that trust flourishes business.

Therefore let your conscience towards this proposal be nurtured with sincerity and I will not fail to bring to your notice that, this transaction is hitch-free risk and you should keep this transaction ( CONFIDENTIAL) why because, no other person know about it, its a business between you and myself only for the safety and security of the business. I agree that 35% of this money will be for you as a foreign partner, in respect to the provision of a foreign account where this fund will be transfer into, and 65% will before me, thereafter I will visit your country for disbursement according to the percentage indicated. Remember, you will apply first to the bank for the transfer and my career as a banker, I will bring you up to date with all the information's as soon as I hear from you. If I don't hear from you within a certain period, I will assume, you are not interested.

Blunt Trauma #3, 2010, Oil and acrylic on panel with video on custom media player, 24 x 20 inches