Jan de Cock, Denkmal 11, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, 2008, Module CDLIX, January 22 – April 21, 2008

The young Belgian artist Jan de Cock (b. 1976) has shown in many European venues over the last several years, including the Tate Modern in London and De Appel in Amsterdam. This exhibition at MoMA is his first major show in the United States. Landing on our shores after having achieved the status of a distant but persistent rumor, if not quite a cult item, his work turns out to be compellingly erudite, tasteful and clever. But after the first flush of formal audacity wears thin, it unfortunately registers as an emotional dead end, dry and airless, failing to find resonance beyond its own hermetic self involvement.

The exhibition is notable for its physical elegance, austerity and pristine production values, and for offering a tantalizing vision of an ambitious, overarching intelligence that hopes to organize our knowledge of contemporary art into a latter day, dandified Cabinet of Curiosities, a complex archive of images and references. Still, it is a brittle and impersonal effort, feeling reactionary and forbiddingly over determined.

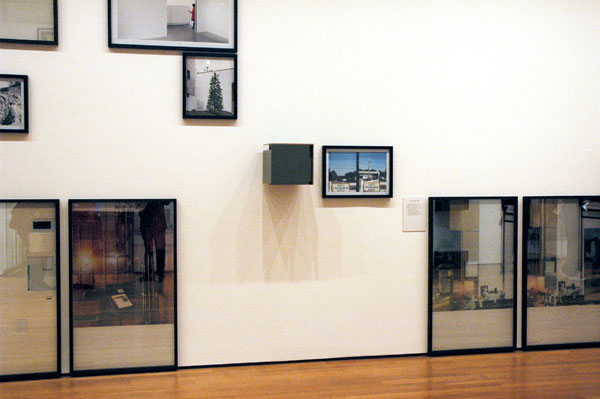

The artist generally creates floor-to-ceiling installations of impeccably framed and matted photographs of art work, or more accurately of images and fragments of images culled from a particular collection of art. As its very long title suggests, the exhibition is both in and of MoMA: the museum is its self reflexive subject. In order to produce his archive, de Cock visits unexpected locations, photographing not only in the galleries but also referencing the museum’s architecture, film theaters and library, and showing us work in behind-the-scenes situations, such as the conservation lab or frame shop. Also included are shots from his previous European installations (he does not mind recycling) and other historical material, often with a winking, suggestive agenda. For example, frequent images of Kurt Schwitters can only remind us of the collage-like structure and layering of images found in de Cock’s own oeuvre.

The exhibition is notable for its physical elegance, austerity and pristine production values, and for offering a tantalizing vision of an ambitious, overarching intelligence that hopes to organize our knowledge of contemporary art into a latter day, dandified Cabinet of Curiosities, a complex archive of images and references. Still, it is a brittle and impersonal effort, feeling reactionary and forbiddingly over determined.

The artist generally creates floor-to-ceiling installations of impeccably framed and matted photographs of art work, or more accurately of images and fragments of images culled from a particular collection of art. As its very long title suggests, the exhibition is both in and of MoMA: the museum is its self reflexive subject. In order to produce his archive, de Cock visits unexpected locations, photographing not only in the galleries but also referencing the museum’s architecture, film theaters and library, and showing us work in behind-the-scenes situations, such as the conservation lab or frame shop. Also included are shots from his previous European installations (he does not mind recycling) and other historical material, often with a winking, suggestive agenda. For example, frequent images of Kurt Schwitters can only remind us of the collage-like structure and layering of images found in de Cock’s own oeuvre.

The photographs are periodically interrupted by intricately constructed plywood boxes which actively reference a Modernist continuum, from the furniture designs of Gerrit Rietveld to the minimalist sculpture of Donald Judd. Like the photos, the boxes are hung throughout the space in various postures: individually, in vertical or horizontal series, and at different altitudes. One particularly large version sits on the floor like a Constructivist tree house fallen on bad times, obstructing the portal between the two exhibition spaces. Another is wedged near the ceiling next to the EXIT sign. This floor-to-ceiling imperative, which forces viewers to either sharply crane their necks or bend over like an ostrich, even manages to encircle permanent wall texts like “The Robert and Joyce Menschel Gallery” in its amoeba-like sprawl: certainly an unexpected but effective way of getting closer to one’s patrons.

De Cock’s images are carefully framed, cropped and juxtaposed. The same object can be shot from different angles or distances and then presented as a diptych, suggesting a filmic or narrative progression, implying motion or the passage of time. Sometimes the mats are specially cut, peekaboo style, to obscure part of the photo, which appears as a fragment or an extreme close up, often included in the same frame with other similar fragments. And throughout the room there are frequent rows of black framed photos, hung serially to suggest a film strip.

De Cock’s images are carefully framed, cropped and juxtaposed. The same object can be shot from different angles or distances and then presented as a diptych, suggesting a filmic or narrative progression, implying motion or the passage of time. Sometimes the mats are specially cut, peekaboo style, to obscure part of the photo, which appears as a fragment or an extreme close up, often included in the same frame with other similar fragments. And throughout the room there are frequent rows of black framed photos, hung serially to suggest a film strip.

Despite these obvious cinematic influences, de Cock works as a sculptor and photographer. But he claims to be informed by film theory enunciated by Gilles Deleuze and Henri Bergson, and has described his own work as “film montage in space”. In an interview with MoMA photography curator (and organizer of the exhibition) Roxana Marcoci, he cites a debt to Jean-Luc Godard, particularly to late efforts such as the four hour Histoire(s) du cinema, which he describes as “a soaring collage of film clips and stills, music fragments, sound effects, on-screen text, and voice-over”. In the same interview, he traces his lineage back to proto-cinema pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, whose work, in fact, is visible in an adjoining gallery displaying MoMA’s permanent collection of photography. One imagines this extracurricular addition as a friendly nod from the museum’s curatorial staff.

De Cock’s installations also resonate on the level of syntax: the photographs like words, the plywood boxes as punctuation marks, the overall groupings suggestive of sentences. These groupings are gathered into even larger clusters, called Modules, each being assigned a Roman numeral and a very precise time signature, which generally appear as part of the piece and are also included in the titles. Finally, the Modules are organized into a single volume encompassing the entire exhibition. This particular show at MoMA is entitled Denkmal 11, a reference to the museum’s address at 11 West 53rd Street, and comprises fourteen Modules, numbers CDXLVI through CDLIX. I will leave you to do the Roman math.

De Cock’s installations also resonate on the level of syntax: the photographs like words, the plywood boxes as punctuation marks, the overall groupings suggestive of sentences. These groupings are gathered into even larger clusters, called Modules, each being assigned a Roman numeral and a very precise time signature, which generally appear as part of the piece and are also included in the titles. Finally, the Modules are organized into a single volume encompassing the entire exhibition. This particular show at MoMA is entitled Denkmal 11, a reference to the museum’s address at 11 West 53rd Street, and comprises fourteen Modules, numbers CDXLVI through CDLIX. I will leave you to do the Roman math.

These arcane details might possess a peculiar fascination for fans of the Dewey Decimal System and other paradigms of academic classification. But they certainly illustrate the obsessive systems underlying de Cock’s art. “Denkmal”, the word he uses to title each of his installations, the seeming apex of his classificatory pyramid, means “monument” in German. It is not an actual word in his native Flemish, but loosely translates as “think mold” (from “denk” and “mal”) or better yet, “thought mold”.

Both translations add something to our understanding of the art. “Monument” is way too grand, of course, but if meant ironically it recalls the iconoclastic work of Marcel Broodthaers, also a Belgian. Institutional critique has certainly proliferated since the 60s, when Broodthaers parodied the museum system with his bombastic, ironic, neo-surrealist installations, and the creation of a “Museum of Modern Art: Department of Eagles” in his Brussels home. Considering the recent work of Andrea Fraser, Renee Green, Fred Wilson, Louise Lawler et. al., it’s hard to say how de Cock’s tepid examination of the museum’s collection will further our perception of the institution. But it does recall a recent curatorial effort at MoMA by architects Herzog & de Meuron. Their exhibition, Perception Restrained, also advanced a certain supercilious dryness and an overstuffed strategy, jamming work together and placing it where it could not be easily seen, to comment on the distance between the viewer and the museum, between the audience for art and its august gatekeepers.

“Thought mold”, the Flemish connotation for Denkmal, leads us down another path. A mold is something which shapes its contents, and the connotations for the artist’s conceptually based program are obvious. But a mold is also something you need to break in order to free the object within, allowing it to be born. If you are overly addicted to the mold, if you cannot break it, then you condemn the object to suffocation and death. It is this second step which eludes the artist and causes certain problems. De Cock is a navel gazer, self referential and internalizing. His art is almost fetishistically hermetic, a closed system of references and rules that bathes in inaccessibility and obdurately shrouds its meaning behind shifting layers of obscurity. It is a secret rebus waiting to be deciphered by a code. Yet his effort is also encyclopedic and archival, which by necessity needs to refer to an external source of images.

Both translations add something to our understanding of the art. “Monument” is way too grand, of course, but if meant ironically it recalls the iconoclastic work of Marcel Broodthaers, also a Belgian. Institutional critique has certainly proliferated since the 60s, when Broodthaers parodied the museum system with his bombastic, ironic, neo-surrealist installations, and the creation of a “Museum of Modern Art: Department of Eagles” in his Brussels home. Considering the recent work of Andrea Fraser, Renee Green, Fred Wilson, Louise Lawler et. al., it’s hard to say how de Cock’s tepid examination of the museum’s collection will further our perception of the institution. But it does recall a recent curatorial effort at MoMA by architects Herzog & de Meuron. Their exhibition, Perception Restrained, also advanced a certain supercilious dryness and an overstuffed strategy, jamming work together and placing it where it could not be easily seen, to comment on the distance between the viewer and the museum, between the audience for art and its august gatekeepers.

“Thought mold”, the Flemish connotation for Denkmal, leads us down another path. A mold is something which shapes its contents, and the connotations for the artist’s conceptually based program are obvious. But a mold is also something you need to break in order to free the object within, allowing it to be born. If you are overly addicted to the mold, if you cannot break it, then you condemn the object to suffocation and death. It is this second step which eludes the artist and causes certain problems. De Cock is a navel gazer, self referential and internalizing. His art is almost fetishistically hermetic, a closed system of references and rules that bathes in inaccessibility and obdurately shrouds its meaning behind shifting layers of obscurity. It is a secret rebus waiting to be deciphered by a code. Yet his effort is also encyclopedic and archival, which by necessity needs to refer to an external source of images.

In trying to bridge two different impulses, the encyclopedic and the hermetic, the artist has stumbled over an untenable contradiction. Considering his complex interrogation of the very process of image making and the parameters of display, perhaps this is exactly his point. Having conceived the work, with its many internal rules and rhymes and borrowings, and its assiduously overlapping theoretical frameworks, perhaps he cannot conceive of arriving at anything as simple as final closure or a definitive interpretation. This would mean breaking the mold he so carefully constructed.

The artist seems pleased to strand us in a fashionably pessimistic no man’s land, like the end game of a Samuel Beckett play, where all roads lead to stasis, inertia and melancholia. Perhaps you buy into this. I need more. But whether or not we judge it a complete success, de Cock’s effort is never less than fascinating in its scope and ambition. And, on a lighter note, since his work requires a surfeit of preparation, art framers and matters will never go hungry when de Cock is in town.

The artist seems pleased to strand us in a fashionably pessimistic no man’s land, like the end game of a Samuel Beckett play, where all roads lead to stasis, inertia and melancholia. Perhaps you buy into this. I need more. But whether or not we judge it a complete success, de Cock’s effort is never less than fascinating in its scope and ambition. And, on a lighter note, since his work requires a surfeit of preparation, art framers and matters will never go hungry when de Cock is in town.

De Cock himself is very much a “modern jazz creation”, as mentioned by Colin MacInnes in his novel Absolute Beginners: thin ascetic face, long dark hair, black jacket and jeans, white shirt, skinny black tie. All sharp edges, quick mental acuity, and hipster nervosa. As the MoMA opening was winding down, I heard the words “after party” and “Blue Note”, a famous jazz club in the Village. Since I had spoken with him previously, I asked the artist if he was planning a trip downtown. His reply: the party would not be at the club, but rather in his hotel room, to listen to some Blue Note jazz CDs which he had just bought in New York. A perfect response, in a way: not an actual performance but an archived gig, not a public venue but a private chamber, and not the original but rather its label, its representation.

[Photos courtesy of James Wagner.]

[Photos courtesy of James Wagner.]