Elgaland – Vargaland in Venice

A frequent critique of the Venice Biennale is its organization into national pavilions. As a legacy of the first Biennale of 1895, when nations were young, naive, and given to a prideful beating of their imperial wings, the idea of identifying particular art with a particular country and then competing for the best of show, a Golden Lion, might have once seemed appropriate. It now seems wholly anachronistic. In our current climate of globalization, of multi-national corporations and commissions funding large exhibitions in far flung territories, of curators and artists hopping from one project and one continent to another, segregation according to nationality appears somewhat fusty and quaint.

An acquaintance of mine, an art restorer who has lived in

Of the 77 official national entries to the 2007 Biennale, some were mounted in their usual pavilions in the Giardini. Others rented spaces throughout town. But only one – a 78th and decidedly unofficial entry -- planted its flag on the Isola de San Michele, the island of the dead that is

According to its constitution (which can be found, together with lots of other major and minor arcana, at http://www.elgaland-vargaland.org), KREV was founded in 1992 as a dual monarchy (with LE as king of Elgaland, and CMvH of Vargaland), claiming as its political territory all national borders and demilitarized zones (e.g. between North and South Korea), a strip of ocean beyond the ten mile limit, and other frontier areas established by international law. Also annexed, as part of the kingdom’s mental realm, were indeterminate states of being (such as that between sleep and wakefulness) and, in the virtual realm, digital space. Typical of their continual expansionist mode: just a few weeks before the Biennale, the French ambassador of KREV formally annexed l'étale, that portion of the strand between high and low tides.

Anything unclaimed or of ambiguous ownership seems fair game. KREV exists in the interstices of space and time, in a physical and virtual no man’s land, and constantly seeks to expand its domains. Benevolently of course, so that all might eventually share the joys of immortality and complete freedom guaranteed to its citizens. The KREV imperative is utopian and reductive. In theory, once the entire world is subsumed under KREV, all boundaries will cease to exist. We will all be one.

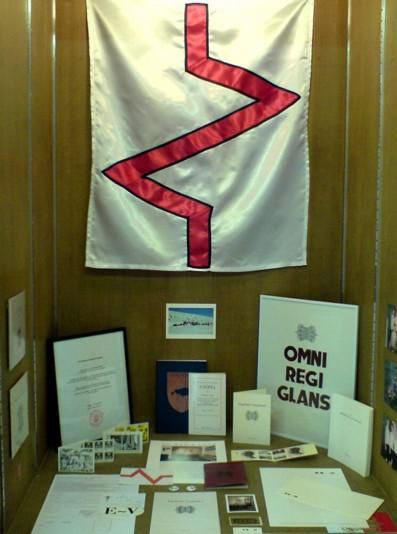

KREV revels in the panoply of statehood. It has a flag (a red blip against a white field), a coat of arms and various versions of a national anthem (including one by a mariachi band). Currency, stamps and passports have been issued and reissued. Monuments have been placed. Over the years, embassies and consulates have sprung up throughout the world, generally simultaneous with an exhibition of KREV paraphernalia at an art gallery or konsthall.

Citizens (mainly artists, dealers, curators and critics) currently number over 850, seeming proof that, even in the elevated and anti-authoritarian precincts of the art world, many enjoy the pomp and circumstance of a royal parade, however tongue-in-cheek. For some unknown reason, passport applications have been closed since Christmas 2006. Did the royal locksmith go on permanent vacation and throw away the keys?

A semi-legalistic jargon characterizes KREV proclamations and manifestos, an indication of its healthy tolerance of nonsense, as also shown in the naming of a national drink (vodka and coke), a national dish (pasta with ketchup and garlic) and the titling of its ever expanding bureaucracy. There are, for example, Ministers of Bloody Marys, of Lamination, of Astral Projection, of Memory Lapse, of Holes, of Pedantry, of Shagging – and of Nothing. Although nominally part of a virtual autocracy, every citizen (or Minister) seems free to choose their own path, their own fantasy. It makes for some quirky choices.

The underlying irreverence of these choices, and of KREV’s overall parody of nationhood, offers a droll critique of government, citizenship and political power, and implicitly subverts the self importance of a high profile event like the Biennale, which insists on enshrining the primacy of the nation state. So that the annexation of a cemetery, the ultimate no man’s land, by a fictional monarchy founded on indeterminism, seems a ready made intervention, just waiting to happen. It makes one wonder why 2007 was KREV’s first performance during the Venice Biennale, even if the actual “performance” consisted of little more than the two “kings” arriving by boat, photographing famous graves (Ezra Pound, Igor Stravinsky) and enjoying a light picnic. Sometimes less is more. But the dead did not just arrive at the Isola de San Michele and were not leaving anytime soon. So how did this become KREV’s Death in Venice moment?

The answer possibly lies in the personal careers of LE and CMvH, who have both been

From a slacker perspective, KREV is fascinating for its studied indolence, its quasi-adolescent embrace of “playing government” (a step up from “playing soldier”), and the dry hilarity and inexorable logic of its annexation ceremonies, all of which advance the conceptual underpinnings of the kingdom. Even the iconography of its flag, a squiggly red line, graphically summarizes the logic of the state. Find a map and trace the border of any country with red pencil. You have drawn part of KREV’s imaginary realm. Trace other national borders and you add to that realm. Draw the line ten miles out at sea and you have defined its watery realm. Extend the line forward or backward in time and you have a history of changing frontiers (the result of wars, revolutions, treaties), all of which are also claimed. The beauty of the conceit is that history will always create new borders, and KREV will always be there to annex them.

KREV combines a throwaway simplicity with the appetite of an anarchic landlord, ready to claim whatever falls through the cracks. This confluence of subversion and practicality unites them with other art projects based on unclaimed territory, on the elaborate fiction of property, or on the construction of imaginary nations. Projects such as Gordon Matta-Clark’s Fake Estates, Gregory Green’s New Free State of Caroline, and the NSK/Laibach collective. But none of these others managed to arrive in