Looking at Art with Jacques & Pierre, or Vision Thing

Artist's Choice: Herzog & de Meuron, Perception Restrained

Museum of Modern Art, New York

June 21 through September 25, 2006

Museum of Modern Art, New York

June 21 through September 25, 2006

In our contemporary secular climate -- post modern, post faith -- art has assumed some of the duties of religion. It channels our vision, informs us what is "really there" behind the veneer of mere appearance. It anoints us with significance. But should art stand in for faith, who will be its theologians, its explicators or apologists? Who will inform the masses?

The artists themselves? Artists certainly do not lack the ego to don priestly vestments. But many are too solipsistic, too insular, and too impatient to provide a useful model for pedagogy. If the audience doesn’t "get it" right away, artists often can’t be bothered to explain. In fact, the very act of explanation might be viewed with suspicion: as pandering, as a capitulation or failure. Since, in the typically austere model, the work’s intrinsic and visible qualities should be strong enough to obviate any need for explanation. What’s more, the elitist mechanism of the art world does not particularly encourage or reward artists for explaining their metaphysic to the world at large. Their target audience is smaller, although more rarefied. As long as they are able to impress one dealer, two museum trustees, three critics, four curators and five major collectors, everyone else will surely follow in due course.

The role of public advocate is more readily assumed by architects. They are inured to the necessities of a client relationship. Architects, even star architects with a Pritzker in their portfolio, constantly need to sell the importance of their work to government committees, corporate presidents, zoning boards and the like. And while architects do not lack for ego, they must be ready to socialize, to defend and cajole and explicate, to offer up a persona for public consumption. Perhaps that’s why so many invest in designer eyewear, as a talisman of their unique vision. If we can believe their jargon, and their eyeglasses, we are well on the way to approving their designs for living.

What would happen if architects were allowed to curate an art show? Would they become more dogmatic and unapproachable? Would they maintain their typically conflated posture: true visionary meets super salesman? Or would other factors intervene?

The particular case study is Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, of the respected, well known Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron. They have designed the Tate Modern in London, the extension of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the de Young Museum in San Francisco, the Schaulager kunsthalle in their hometown of Basel. As well as various sports arenas (in Germany, Switzerland and Beijing – the last in progress for the 2008 Olympic Games), plus apartment buildings, private residences, factories, schools, office buildings. They are currently engaged in the design of a condominium/townhouse complex for Ian Schrager and Aby Rosen in New York’s NoHo neighborhood, and of the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton. They have their Pritzger (2001). But the one commission that eluded them, the prize just out of reach, was the expansion of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, perhaps the world’s foremost temple of art. Their design made it into the final three, but they ultimately lost to Japanese architect Yoshio Taniguchi.

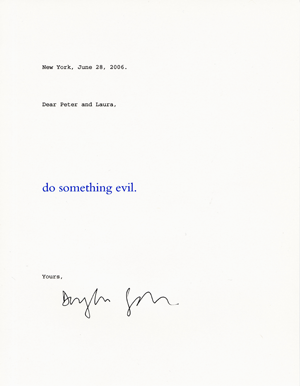

Perhaps as a peace offering, to indicate they are still held in high esteem by the museum’s mandarins, H&dM were tapped to curate an Artist’s Choice exhibition at MoMA. This is only the eighth Artist’s Choice since the inception of the series in 1989, and they are the first architects so chosen. What they make of this opportunity is Perception Restrained, a particularly trenchant critique of institutional power and of the conventions of viewing art in a museum. The exhibition, which perversely crams art works into walled off sepulchers where they are essentially hidden from view, or else places them high on the ceiling, touches on a number of loaded issues. On visibility and invisibility, on Situationism and the society of the spectacle, on the postmodern packaging of culture, on the preciousness of the art object, on the fortress mentality of the museum.

Most tellingly, Perception Restrained is an archly conceived exercise in petulance, an elaborately intellectualized expression of sour grapes. But what else did MoMA expect? With a self conscious gesture reeking of noblesse oblige (seemingly patting themselves on the back while admiring themselves in the mirror -- not an uncommon posture for many MoMA personnel) they graciously extended the olive branch to H&dM, beckoning the architects back to the house they did not get to build. H&dM responded in an all too human way. They bit the hand (that didn’t feed them), but with cunningly deadpan subversion and piss elegant politesse. The rarefied pas de deux between all powerful, super rich patron and aggressively intelligent servant, set in the higher precincts of the cultural elite, has hardly been demonstrated to better advantage. And, as H&dM can hardly be unaware of the recent critical backlash against Taniguchi’s design, it is certainly a propitious moment for institutional critique: right inside the lost commission, the "scene of the crime".

Artist’s Choice is a long running but relatively infrequent series at MoMA (as compared to, say, the Projects). Particular artists have been asked to draw work from the museum’s collection, in order to illustrate a thesis or to reinterpret the collection in the context of their own work. It started in 1989, when Kirk Varnedoe invited Scott Burton, the sculptor of benches and plinths, who responded with an exhibition of Brancusi’s bases as sculpture in their own right. Subsequent exhibitions were organized by Ellsworth Kelly (1990), Chuck Close (1991), John Baldessari (1994), Elizabeth Murray (1995), Mona Hatoum (2004), and Stephen Sondheim (2005).

H&dM certainly fulfill the mandate on contemplating the meta- with Perception Restrained. As might be anticipated from architects, it is the manner of display rather than the actual art selected for display that they find instructive and essential. H&dM make it clear, in their accompanying brochure, that the choice of objects in the show does not reflect any personal aesthetic preference. "Everyone knows that the holdings of MoMA are unparalleled in quantity, quality and density. How could we possibly pick out the gems when we only have gems to choose from?"

So while art is the ostensible subject, this is decidedly NOT an art review, as the selection seems almost incidental. The art serves merely as a prop for the real issue, which is space. Space energized for display. The spectacle, and the paradoxical failure, of exhibition. H&dM never actually engage in a direct critique of the Taniguchi galleries at MoMA. This would be unseemly, ungracious and decidedly uncollegial. They instead choose to locate the problem with the viewer. "The problem facing the Museum is not a lack of first-rate art but rather a lack of perceptive attention on the part of museum visitors, despite the spectacular galleries in the new extension. The art is there, spread out in a panorama, professionally illuminated, impossible to overlook – but it is not seen."

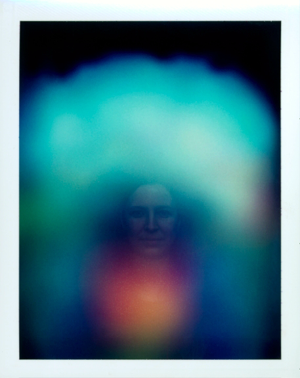

The unfortunate, clueless visitor just won’t concentrate! Great riches are laid out before him, but he won’t pay attention. (H&dM obviously refer to the casual museum attendee, and certainly not to their peer group of art adepts or aficionados, whose practiced eyes will never waver from the prize). The solution? Make the art less accessible. Make viewing it a challenge, through simple spatial dislocation and interference. "Our project is an attempt to offer a spatial alternative to the existing galleries for a limited period of time and in a limited space, a site of heightened concentration and density that functions like a kind of perception machine. By obstructing and putting pressure on perception, the installation intensifies the viewing experience and makes it more enduring, more selective, and more individual." In other words, hide the art, or at least obscure it, in order to foreground the very act of viewing. Purify the experience by making it an ordeal, a trial. Create difficulties to vision, because only then, with the consciousness of surmounting a barrier, will the audience become truly aware and appreciative of the art on display. Less (visible) is – you know – more (visible).

The main, entry space of Perception Restrained is a dark room filled with rows of long benches. Fifteen video screens are mounted on the ceiling, with loops (ranging from 37 seconds to 14 minutes) excerpted from various Hollywood blockbusters and a limited avant-garde repertory. Included are three ultra violent, kinetic scenes from Scorcese’s Italian-American urban crime melodramas -- Goodfellas, Taxi Driver, and Mean Streets. The Robert Duvall intoned "I love the smell of napalm in the morning" air cavalry attack from Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. The bullet ridden finale of Bonnie and Clyde. Werner (no relation to Jacques?) Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Woyzeck (both starring Klaus Kinski). A trinity of Warhol films from his Paul Morrissey period: Trash, Flesh and Heat. And of special interest to a Swedish audience: Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious films, both Yellow and Blue. In order to view the clips, one must either crane one’s head upward, lie flat on the bench, or use thoughtfully provided hand mirrors to reflect the images above.

H&dM indicate the choice of films does not reflect their artistic taste (although the art house selections do seem a fond relic from their student days), but "simply confirms an undeniable shift in imagery that has taken place in recent years. The moving image with explicit reference to violence, drama, and sex has received growing attention while traditional artistic mediums require special exhibitions with blockbuster potential in order to be perceived at all."

Aware of its potential to educate, propagandize and create revolutionary consciousness, Lenin called film "the most important art". H&dM seem to agree, but ruefully. The vulgarity and accessibility of film is a fashionable gripe among the chattering classes. Its inherent noise and motion allow it to dominate other forms. But film is just the appetizer to this show. Off to the sides of the central viewing room is the main course, the meat, potato and veggie: three sequestered chambers, viewed through horizontally slotted windows or apertures reminiscent of castle crenellations. Objects are stuffed into these semi accessible, "perceptively restrained" vaults in super salon style, cheek by jowl, with the haphazard density of a dragon’s treasure trove, and are segregated according to the logic of MoMA’s own curatorial departments. One bunker contains examples from Architecture and Design (45 objects), the second has Photography (36), and the third has Painting and Sculpture (25). The history of modern art in 109 easy pieces, courtesy of MoMA and H&dM.

In the design vault are chairs by Alvar Aalto, Charles Eames, Verner Panton and Arne Jacobsen. An Ettore Sottsass portable typewriter. William Morris's Strawberry Thief printed fabric. A cake service and TV from Philippe Starck. Some original Tupperware. A wheelbarrow from Gerrit Rietveld. A spatula from Karlsson & Nilsson, and (in a discreet nod to themselves) a maquette in folded copper of one of H&dM’s early commissions, a railroad signal depot in Basel.

The photography bunker contains few surprises. The expected names all contribute (except there is nothing from Robert Frank. Why?). Diane Arbus, Man Ray, Lee Friedlander, Edward Weston, William Eggleston, Robert Adam, Robert Mapplethorpe, Larry Clark, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, Cindy Sherman, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Gregory Crewdson, Collier Schorr, Gillian Wearing, Oliver Boberg, Rineke Dijkstra.

In the rarefied Painting and Sculpture vault, only the strong survive. A Cézanne self portrait. Picasso’s paper maquette for his sheet metal Guitar sculpture. Matisse. Mondrian. A Giacometti bronze. A Balthus portrait of Joan Miró and his daughter. Dali, Calder, Louise Bourgeois, Frida Kahlo, Joseph Beuys. A Francis Bacon study. Pollock, de Kooning, Ad Reinhardt, Franz Kline. Jasper Johns. Donald Judd. A Warhol self portrait silkscreen. A Gerhard Richter landscape. Sculpture by Bruce Nauman, Jeff Koons, Robert Gober, Charles Ray, Matthew Barney.

An exhaustive (and exhausting) list, but not particularly revelatory, because the choices are drawn from artists and designers well known within the modernist and postmodernist canon. The objects are already spoken for. They have a place in art history and an appreciable, collectible value. Could this be the very point? The Swiss are bankers to the world. Perhaps it is no accident that H&dM feel most comfortable placing the work where it will be safe, in a protected, inaccessible bunker. It is their reaction as good citizens of MittelEuropa. Architects are devout servants of capital, of real property. Their livelihood, after all, is in the creation of more real property.

But let us take H&dM at their word, and view their entombment of the object as paradoxically liberating, even a bit subversive, because it makes us see the work from a new perspective. Let us also accept their critique of spectacle, and of the packaging of culture in our contemporary, image saturated society: that in order to compete with film, other art forms must establish a new density, or be incorporated into a new blockbuster format, in order to signify to the mass audience and thus aggrandize the exhibiting institution. This thesis would hopefully be illustrated by the physical parameters of Perception Restrained. But in fact the objects in the bunkers are not as easily seen as the film clips above our heads, which again win by default. Not exactly the liberation of the object as posited by H&dM. In this case, at least, their theoretical musings on perception seem to outstrip their praxis.

But in their institutional critique, H&dM seem right on target. Like the universe at large, MoMA has periods of expansion and contraction. The cosmology of the museum, if you will. In its shiny Taniguchi shell, MoMA might seem poised on the cusp of a new era of exploration: to boldly go where no institution has gone before. But space is a funny thing. While the museum has stunning interior vistas, atria, and stairways to heaven, as well as a plentitude of cafes, restaurants and bookshops, its actual usable space – as measured in ease of crowd flow, navigability from gallery to gallery, transparency of spatial intentions, sheer ease of use – might leave something to be desired.

In sucking the air out of Perception Restrained, H&dM are sounding a cautionary note: that claustrophobia might soon be the order of the day throughout the entire museum, with its huge permanent collection, its expanding public, and its archaic, departmentalized organization. The new MoMA might already be outmoded, and ill equipped to survive a population explosion in its audience. The argument is positively Malthusian, but no less compelling. To paraphrase from a film H&dM did not show on their ceiling: "Soylent Green is art."